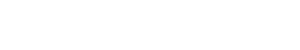

The director will present his latest film “The End of the World” in Sofia along with a retrospective at the Czech Centre

Bohdan Sláma is one of those emblematic directors who continues the traditions of the Czechoslovak New Wave and has earned the recognition of experts and film forums around the world. For his feature debut, Wild Bees (2001), he won the “Tiger Award” at the Rotterdam festival. His successful career as a director has spanned more than two decades. For his film Something Like Happiness (2005) he was honored with the “Golden Shell” in San Sebastián. His filmography includes The Country Teacher (2007), Four Suns (2012), Shadow Country (2020), and Dry Season (2024). Since 2008, Sláma has been a lecturer and Head of the Directing Department at the renowned film school in Prague – FAMU.

Between March 10 and 14, in partnership with the Czech Centre – Sofia, a retrospective featuring five of Bohdan Sláma’s films will be presented in its cinema (free admission), and on March 15 at Odeon Cinema the international premiere of his latest film The End of the World will take place, during which Sláma will receive the Special Award of Sofia Film Fest.

Below is the text dedicated to the work of the Czech director, written by Cvetan Cvetanov:

Bohdan Sláma holds a special place among the generation of Czech directors who started making films during the 1990s and established themselves as global masters of cinema in our millennium. He was born in 1967 – just like Peter Zelenka and Jan Hržejbek, who have long been favorites of Bulgarian film audiences as presented over the years at Sofia Film Festival – and the fact that he came of age during those very years, immediately following Czechoslovakia’s 1968, also carries an unmistakable historical significance.

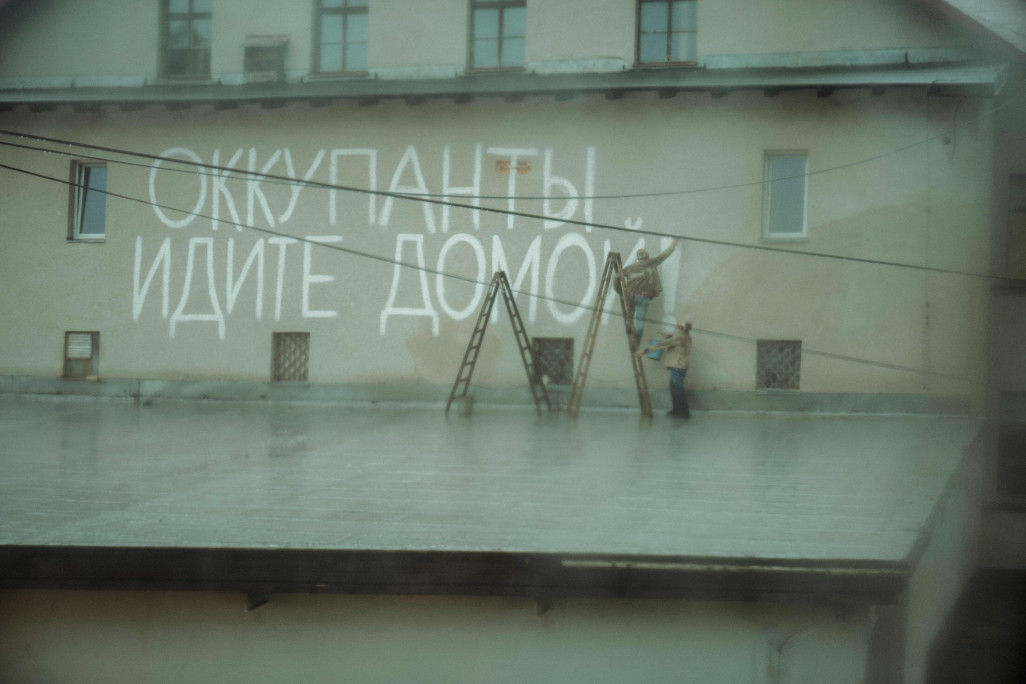

Bohdan Sláma, who visited Sofia 12 years ago—not alone, but together with the legendary Czech post-punk group Vypsaná fiXa, the composers for his film Four Suns (2012), and who screened four of his films (then invited by the Czech Centre, in years when even punk concerts were held in their building)—is from Opava, a town in the Moravian-Silesian Region of the Czech Republic, the historical capital of Czech Silesia. This multicultural environment, with all its natural beauty and its intricate historical causes and effects, seems to serve as a starting point for his reflections on humanity and history in many of his films. The Moravians of the deep provinces appear as protagonists in his early masterpiece Wild Bees (2001); the year 1968, as seen through the prism of life in a “small place” (a village in the Jizera Mountains) in his film The End of the World (2024), where even one of the two main characters is a descendant of Russian nobility (a Czech Lermontov, or even Nabokov, if you will); while the black-and-white historical chronicle Shadow Country (2020) raises the eternal question about those living in limbo during wars and global catastrophes: “Who are we?”

In fact, that question lies at the heart of Bohdan Sláma’s entire work. The conditional distinction between his earlier films (Wild Bees, Something Like Happiness, The Country Teacher, Four Suns) and his most recent works—which Bulgarian audiences will see for the first time at the 29th Sofia Film Fest (Shadow Country, Dry Season, and The End of the World)—is essentially marked by the increasingly prominent historical framework in the last three. “Who are we?”, however, on a more basic, purely human level, is an open-ended question whose answer is sought by the protagonists of all the director’s films, regardless of their age, views on life, affiliation, or social status. And although the world is full of pain, injustice, broken hopes, and the immediate danger of whether we will survive as individuals and as a society, the small islands of humanity and the hope that despite everything we can live together occupy a key place in Sláma’s films. They usually appear at the end, but we believe in them because, unlike the classic commercial “happy ending” found in some Western cinematic traditions, in Sláma’s work they rest on a more solid logic—the logic of nature’s cycle (with all its births, deaths, and rebirths)—and a deeper sensibility, such as the sensibility of the ordinary eccentrics in his films: the “figures from the old world” (as described by Dušan Hanák), a Michael Jackson from Moravia, if you will, the crazy folk healer who “listens” to the stones, the neighbour two houses down who, deceptively, doesn’t even appear eccentric… but look closer.

Cvetan Cvetanov

***

SEE YOU AT THE #CINEMA!

#29SofiaIFF